← go back 'blog'

Second Base

Oh my lord, it's December already. I hate myself.

Engage the ring gfx timeout, signaled sequence, emitted sequence.

Welcome All Who Are Grieving over the fact that a potentially large number of programmers do not know about, or simply don't use, a very handy git feature that might save their repositories (particularly their default branches) from becoming a total mess. This article will introduce and expand on the concept of interactive rebase for use on personal branches used for contributing code to a project's default branch.

But why?

As an example, let us take a basic git repository with a defined default branch, the name of which is typically 'master' or 'main', with the latter being more common these days. The repository hosts a useful piece of software and therefore attracts some users. At some point, one of those users turns out to be someone with development experience. That person is you.

You wanted a feature introduced to the program and wrote the necessary code to facilitate it. Naturally, you have your own branch, likely hosted on your own fork of the repository, and you open a merge/pull request to get review feedback before it's possible to merge the change. This is important because there could be things you might have missed in the process, for example, you might have broken a build for another target (aarch64, macOS, etc.), and nobody wants regressions. Such feedback could also help assist you with adjusting your coding style to match the program's, so on and so forth. That much is probably very clear.

However, once a reviewer provides help, how do you go about applying it to the branch? From my experience, a lot of people simply push more and more commits, the more feedback they get. This can get very ugly, very quickly, e.g. your feature might require edits in multiple files, it can depend on other features, it might also fix a bug or two as you're starting to understand more of the original code.

If you choose the way of commit spamming your branch here, you run into the risk of making your edits incredibly difficult to bisect if anything goes wrong later on after merging your feature.

There does exist a way to make this issue disappear: squashing. Many repository hosting solutions, such as GitHub or GitLab, contain this feature, usually located very close to a 'merge' button. This operation takes all MR/PR commits submitted as part of a branch and creates one larger commit containing the necessary changes after all review feedback has been addressed.

There are two issues with this approach, however. Firstly, this prevents parts of your change (i.e. potential bugfixes) to be easily backported (or even cherry-picked) to a stable branch of the code, which is a very common practice found in many projects, such as the Linux kernel, KWin or Mesa. Secondly, the problem of re-integrating changes from the default branch (which is required to avoid merge conflicts) is not resolved by using squash-and-merge; you are still in need of a tool for this.

Merge conflicts may be resolved by setting pull.rebase to false and simply using git pull origin [default branch], but that will create a very complicated history for your branch and it's not a very clean solution. The least complicated way to edit and reorder commits is taking advantage of git's interactive rebase functionality.

Rewriting history

After setting the EDITOR environment variable to a terminal-based editor of your choice, for example EDITOR=nano or EDITOR=nvim, you can perform various operations which rewrite the commit history of a branch. The most important ones are git commit --amend and git rebase.

git commit --amend

This one is fairly simple; it 'amends' the topmost commit (branch tip), which means overwriting it with new changes staged with git add.

git rebase

This command takes a branch name and, optionally, the -i or --interactive parameter. By default, simply providing the former allows you to rebase your changes on top of another branch (typically the default one), and resolving any potential conflicts along the way. Executing it after providing both -i and HEAD~N (where N is the number of commits your branch introduces), i.e. running git rebase -i HEAD~3, you are presented with an editable text file that allows you to reorder, edit or drop commits from your branch.

If this is the first time you've become aware of this feature, you might be shocked that rewriting branch history is even a thing. 'How could it be?,' you might ask.

The only branch that ever needs to have protection measures against it is typically just the default branch or an LTS/stable one. Realistically, it makes no sense to try and preserve everything someone has done, because it serves no purpose; what most reviewers want to see is pretty much always the latest revision of your changes to see if their feedback has actually been addressed, and probably nothing else. Sure, there are exceptions to this, such as the Wayland color management protocol discussions and WIP commits for educational purposes, but that is a rare case scenario.

Now, because amending and rebasing do indeed rewrite commit history on a branch, you will be unable to push rebased changes at all unless you provide the -f or --force parameter (there is also --force-with-lease but that's only ever useful for situations where there are many people working on a branch). This is because your local branch's history must be a direct continuation of the remote branch's history (what is present on GitHub/GitLab at any time in your merge/pull request) due to pushes being fast-forward. Force pushing can be a very safe operation, provided that only one person is working on a particular branch, which should be a rule in most projects anyway.

Most repository hosting services actually hold on to earlier commit revisions overwritten by a rebase, they are merely detached from all branches and become orphaned. Accessing them (for historical reasons or for 'funny meme hunting' an angry dev's commit history) is done by pasting the hash of that commit into the URL or by running git reflog [--all] and searching for it.

An example

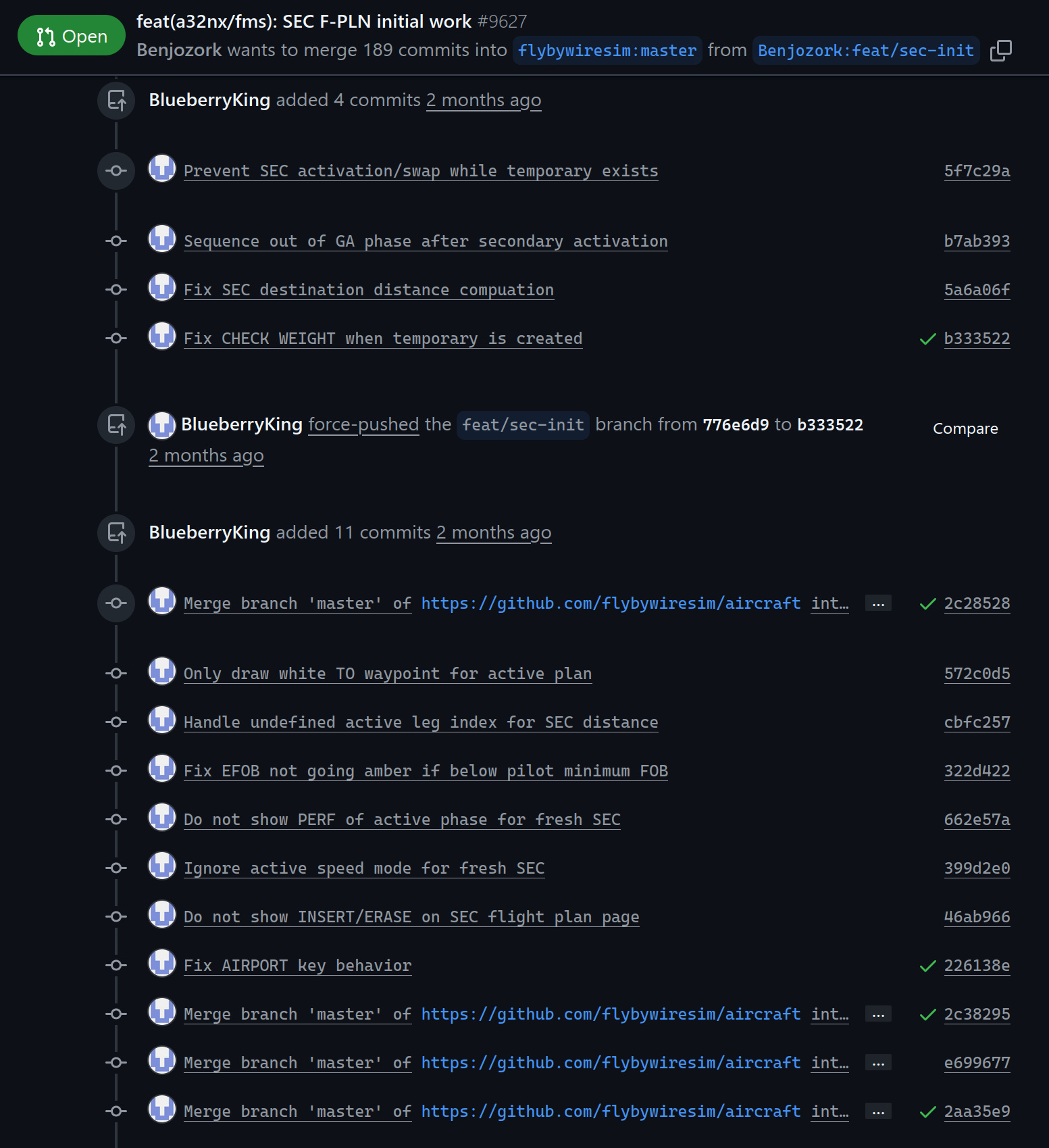

Consider this:

Source

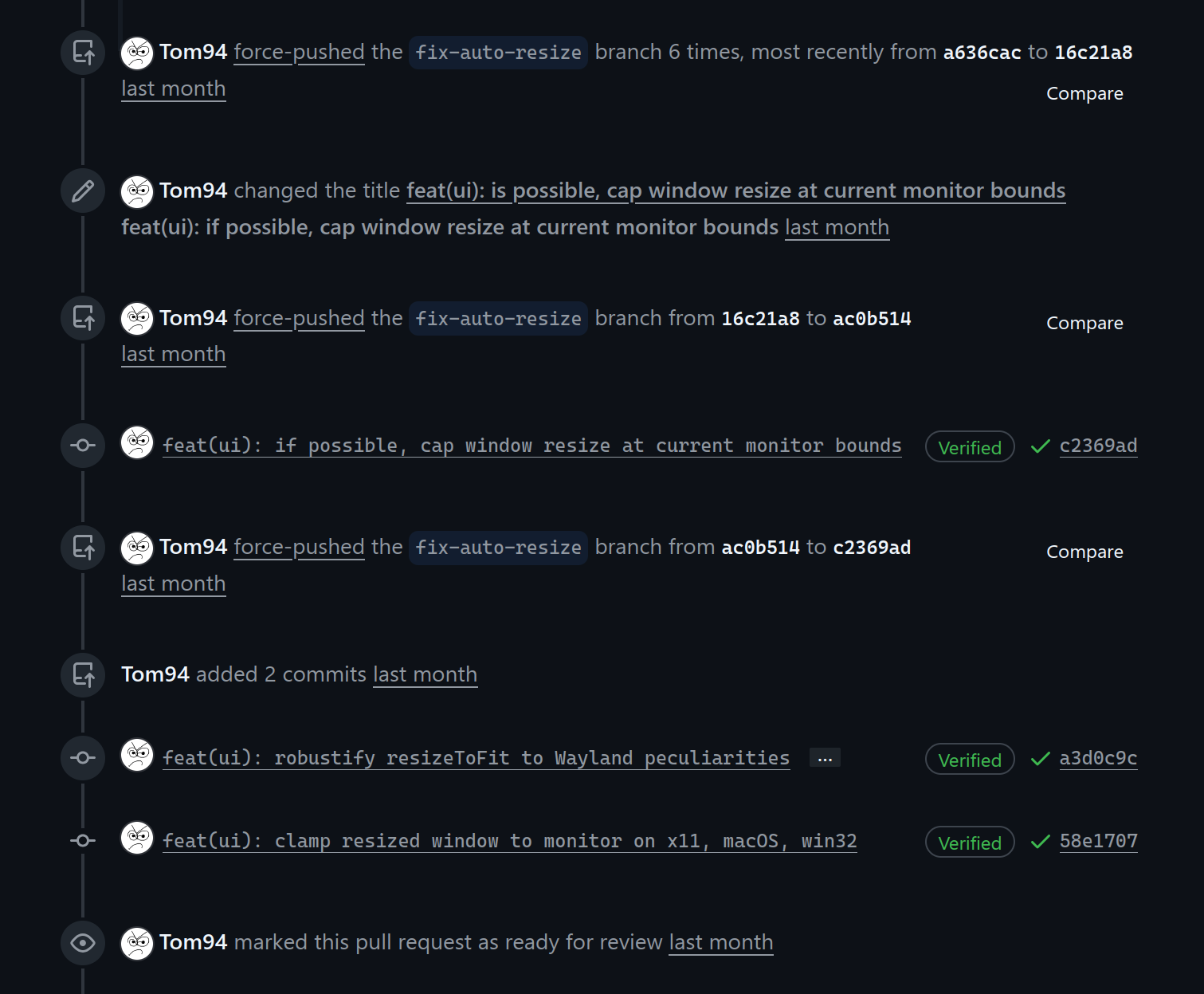

Now compare it with the following:

Source

Notice how much more readable and less cluttered the second example is. This should be the standard, in my opinion.

Fortunately, the project shown in the first screenshot squashes those commits properly and the clutter issue does not manifest itself, so 'all is well'. I'd still argue against using merges and squashes...

Conclusion

Alright, that was a thing. A mini-rant about rebase being ignored in modern code repositories. I hope you learned something from this, have a nice day!

2025-12-01